One of the best known prayers in the Jewish liturgy is the Mourner’s Kaddish. It’s a relatively short prayer, usually said only in a minyan of 10 Jewish adults, who hear the person chanting it and respond. We say it at funerals, in a shiva house, during the mourning period of 30 days to 11 months depending on whom we are mourning, and we say it on the yahrzeit, the anniversary of the passing of a loved one or another person we wish to commemorate.

But why? Why this prayer? How has this little compilation of Aramaic praises of G-d’s great and holy name become so associated with death and mourning? It doesn’t even mention death. We have other prayers that mention the person’s name (for example, the El Maleh Rachamim, which asks for G-d’s compassion and sheltering wings for the soul of the person who has passed). And yet, the one we say over and over is the Mourner’s Kaddish. Why?

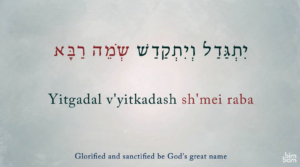

Let’s start by looking at the Kaddish itself. It starts off with a declaration: Magnified and sanctified be the Great Name! This is a reference to the following line from Ezekiel 38:23:

וְהִתְגַּדִּלְתִּי֙ וְהִתְקַדִּשְׁתִּ֔י וְנ֣וֹדַעְתִּ֔י לְעֵינֵ֖י גּוֹיִ֣ם רַבִּ֑ים וְיָדְע֖וּ כִּֽי־אֲנִ֥י יְהֹוָֽה׃ {ס}

Thus will I manifest My greatness and My holiness, and make Myself known in the sight of many nations. And they shall know that I am G-d.

The rest of the Kaddish continues in the same vein, praising G-d’s name and hoping for the establishment of G-d’s kingdom. The congregation responds: May G-d’s great name be blessed for ever and all eternity! This references a quote from Daniel 20:2.

We finish it with the prayer for peace, which is based on a quote from Job 25:2.

So how did the Kaddish become associated with death and mourning? The following is based on an article I found in Moment magazine, by George E. Johnson.

Kaddish seems to have begun its life during Talmudic times as a prayer to be said after Torah study. The first full text of the Kaddish can be found in the Siddur of the Babylonian Rav Amram Gaon, c. 900 CE. However, it later became associated with a 12th or 13th century folktale about redemption in the afterlife. In this story, Rabbi Akiva, who lived in the 2nd century CE, helped free a man who was condemned to be tortured for his sins for all eternity, by teaching the man’s son to say words that are very similar to the Kaddish.

This legend spread like wildfire, with the medieval mindset being particularly excited by the idea of being able to elevate the souls of our loved ones by chanting specific words. In fact, the tradition developed that by saying Kaddish for 12 months, we can save our parents from being punished. That is why we only say it for 11 months – because nobody wants to insult their parents by suggesting that they need our help in this way.

Nowadays, of course, it’s unlikely most people say Kaddish to shield their loved ones from punishment in the afterlife. But it has come to be seen as a prayer of consolation – since it should be said with a minyan, we have to bring ourselves into community, despite maybe wanting to isolate in our grief. It helps connect us to the generations before us, who said Kaddish for their loved ones as well.

My mother passed away in 2003, and my father in 2021. So, as you can imagine, I had very very different experiences saying kaddish for each of them. For my mother, I went to the shul in person, schlepping an infant. I remember having coffee afterwards with all the minyannaires, some of whom were also saying kaddish, and some of whom had said kaddish in the past and now continued to come to support newbies like me. I think if you ask quite a few of the regulars at any shul how they became regulars, there might be some kaddish saying in there somewhere. Our Sages knew the value of a support group long before the word psychology was invented. When you are grieving, community can be a lifesaver.

For my father, I said the entire 11 months on Zoom – here also we have the regulars, the quick schmooze before and after the service begins, although we each provide our own coffee. It’s different, but the feeling is the same. People are there to support each other, and that’s how we make it through grief, together.

So why do we praise G-d’s name in memory of our loved ones? It can be a message of hope, of remembering that it’s a great and mysterious universe out there. We have lots of theories and stories about what happens when we die, but we don’t actually know. The Kaddish reminds us of how we are all connected to something bigger than ourselves.

But truly, in some ways, it seems that the actual words are almost an accident, that they aren’t the most important part. The Mourner’s Kaddish brings us together in community, saying ancient words and hearing ancient responses, the same words and responses that our ancestors said in their time of grief. I believe that that is where the healing magic lies.