Tomorrow we mark the 9th day of the Jewish month of Av (usually called Tish’a b’Av, the 9th of Av), a day set aside in Jewish tradition for grieving and lamentation. While it originally commemorated the destruction of both Temples in Jerusalem on this date (in 586 BCE and 70 CE, respectively), it has become, over the years, an expanded day of mourning. It is considered to be the anniversary of the First Crusade in 1096, the Expulsion from Spain in 1492, the approval of the Final Solution in 1941, and other calamities in Jewish history that happened on or near this date, and generally not a propitious day.

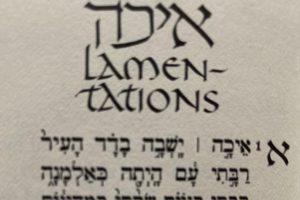

In our time, observance of a day of mourning is not very popular. It can seem forced and performative, and we can feel very disconnected from all of these long-ago tragedies – even the Holocaust is starting to fade from living memory. When we first came to Winnipeg in 1994, the Tish’a b’Av service at our synagogue would be run by a number of Holocaust survivors – they chanted those kinot (dirges or laments) as if they meant them. They are all gone now, and that, in itself, is something to mourn. The number of places in my city where Eicha (Lamentations) will be recited this week is declining, and some of them do not welcome people like me. It is hard for people to find the service meaningful, and it is easier just to ignore our grief, rather than trying to express it in archaic ways. Denial ain’t just a river in Egypt, after all. Can’t we just move on and pretend everything is normal?

That having been said, no matter how hard we deny it, the need to share grief in a public way, especially during this time in which the world is on fire and we are in the midst of a mass disabling event, has not gone away. This piece by Alyx Bernstein, of SVARA, explains beautifully why we need to grieve together, and how the old traditions have become less accessible to us.

Weeping and wailing in the streets is no longer considered an appropriate response to tragedy and loss, and yet the impulse remains. In this late-capitalist, individualistic era, many of the communities that people relied on in the past are gone. People have lost the language that comforted their ancestors. Many of these communities were repressive, and for queer people and women especially it may have been necessary to break free, but loneliness is not the answer.

New communities are being built, online and in person, whether in the form of unions or spiritual fellowship, but it takes time. Right now, this week, how can we channel this grief that so many of us are feeling, in a way that is meaningful for the 21st century? Let’s talk about it.